by Jessica Findlay | Jun 23, 2022 | Ankle |

Do you have pain at the back of the heel?

This is called Posterior Heel Pain and there are actually lots of different causes for pain in this area. There are some common signs and symptoms for each of them. Here we will go through each of them, from most common to least common, so you can work out which problem you might have!

Achilles Insertional Tendinopathy

An achilles insertional tendinopathy is the most common cause of pain at the back of the heel. This is an irritation of where the achilles tendon attaches onto the back of your heel (calcaneous). It is quite different to your usual achilles tendon pain which is typically felt higher up on the tendon, about 2-3cm above the calcaneous. Because the bone AND the tendon are involved, they can be tricky to treat and often take longer.

The symptoms will typically involve pain on initial weight-bearing in the morning, that warms up within 30mins. It may also warm up when beginning running/sport then come on again after a period of activity. They can often ache afterwards.

Unlike a traditional achilles problem, they won’t respond to eccentric calf raises off the edge of a step. You generally have to start with higher range work right up on your toes before slowly dropping down lower as the pain improves. In serious cases, a heel raise worn for a short period can also help settle it down before starting some strength work.

Posterior Ankle impingement

In athletes such as ballet dancers where activity requires frequent rising up onto the tip toes they could experience a syndrome called posterior ankle impingement. This is where both hard and soft tissue can get stuck or “pinched” at the back of the ankle.

Posterior ankle impingement occurs when excessive plantaflexion (pointing the foot) pinches the soft tissue or compresses the back of the joint resulting in a sharp pinching pain.

Os Trigonum at the back of the talus bone.

There are 2 anatomical variations that cause posterior ankle impingement.

- Prominent Posterior Talus. The talus is the main weight-bearing bone in your ankle. The back of this bone can grow in response to abnormal loading. If it grows too much it can start to irritate structures at the back of the ankle.

- Os Trigonum. If the prominent part of the talus grows enough and then breaks off, it becomes labeled as on Os Trigonum. About 20-30% of the population have an os trigonum, with obviously not everyone having symptoms. If however, it does start to cause symptoms, then surgery to remove the loose bone can be highly effective. You can read more about it here https://www.peterlam.com.au/procedures/arthroscopy-of-the-ankle-and-foot/

Both of these anatomical variations can be diagnosed with a plain x-ray.

Treatment will likely include strengthening of the deep muscles in the lower leg such as tibilalis posterior, flexor digitorium longus, flexor hallicus longus and the peroneals.

Severs disease

Sounds “severe” but it’s not! Severs disease an “apophysitis”, or an inflammation/irritation of where the achilles tendon attaches to the back of the heel. When we’re younger, our bones are a bit softer, so repetitive pulling of the achilles tendon on the bone can cause some pain.

Severs disease is more common in boys than girls, aged 8-14 yrs. The typical presentation is pain caused by running, jumping and the pain gets worse with more activity then settles with rest. It often coincides with a growth spurt. As the bones grow, our muscles and tendons can sometimes struggle to keep up, so they get tighter and start to pull on the attachment.

Treatment of Severs disease involves rest from running and jumping until the pain settles, then addressing any tightness and/or weakness of the calf muscles. Sometimes a gel heel cup in the shoe will help offload the attachment. In serious cases, a boot may be required to be worn for 2-4 weeks.

Sural nerve compression

There is a little nerve that runs in behind the heel and tracks towards the outside of the ankle called the Sural nerve. It can be irritated by inflammation from surrounding tissues and normally exists with one of the other pathologies mentioned above or can occur after an ankle sprain (click here for ankle sprain management tips)

The sural nerve will obviously give you nerve pain, which feels very different. Common symptoms of nerve pain are “burning”, “tingling” and “numbness”. We can test the nerve with a nerve tension test and this will reproduce the same pain you are having.

Treatment will normally involve addressing the other problems in the area as well as nerve glides which can help restore mobility to the nerve.

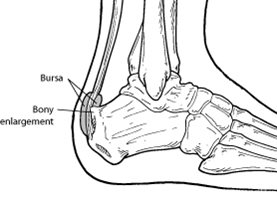

Haglunds Deformity

Haglunds Deformity is a growth at the back of the calcaneuous that causes pain and swelling in the bursa (retrocalcaneal bursitis) and the achilles tendon.

The bone grows due to repetitive stress over the years and can be aggravated by resting the heel on a table or from wearing shoes with a firm heel support.

Treatment involves anti-inflammatories, choosing footwear that doesn’t compress the back of the heel, calf and foot strengthening

and a heel raise to offload the tendon and bursa. In serious cases that fail to improve, surgery may be required to remove the bony enlargement.

Calcaneal bone stress/fracture

A bone stress injury or fracture of the heel is rare and makes it almost impossible to weight-bear.

Pain with weight-bearing, likely with a history of increased load or overload. This one is needed to be confirmed by MRI and you will likely end up with a very fashionable moon boot for 6-8 weeks.

If any of these sound like your pain, then please don’t hesitate to get it seen to quickly.

by Jessica Findlay | Aug 25, 2021 | Incontinence, Pelvic Floor |

1 in 3 women over the age of 45 experience some form of urinary incontinence. There is a great misconception that leakage is a natural part of the ageing process and there is nothing that can be done about it. However, no-one should have to tolerate any form of urinary incontinence and there is actually lots we can do about it!

Urinary incontinence is the accidental or involuntary loss of urine, and can range from tiny leaks to a complete emptying of the bladder.

Risk factors for incontinence can include, pregnancy, pelvic floor trauma after vaginal birth, menopause, hysterectomy, obesity, hormonal changes such as menopause, urinary tract infections, chronic cough, constipation or high impact sport such as gymnastics, trampoline, cross-fit and hurdling to name a few.

Types of urinary incontinence vary, however there are two the main types:

Small amounts of leakage occur during increased intra abdominal pressure, such as sneezing, coughing, laughing, skipping, jumping or running. Basically when the pelvic floor structure has a sudden increase in load of which it cannot take.

This occurs when the detrusor (bladder) muscle contracts unexpectedly, causing a strong sense of urgency and can be accompanied by involuntary loss of urine. Sometimes urgency does not always lead to incontinence, but the sensation of needing to go can lead to small amounts of urine to pass when on the toilet. This can develop into frequency and urgency, also known as overactive bladder. Which means the detrusor muscle is contracting when it shouldn’t be, giving you the over whelming sensation of urge to urinate when it doesn’t need to.

What is the pelvic floor?

The pelvic floor is essentially a hammock of muscle, ligaments and fascia from the front of the pelvis to the back, and side to side. Functionally the pelvic floor supports the bladder neck and anus to help them stay closed. They actively squeeze when you cough/ sneeze/ lift to help avoid leaks from bladder or bowel.

Pelvic floor physiotherapy exercises are now regarded as the first stage of treatment for stress urinary incontinence. For many women, a regular and sustained pelvic floor strengthening program can improve or even entirely overcome the symptoms of stress incontinence. A pelvic floor muscle strengthening program can take 3 to 6 months to change the muscle contraction and its strength.

How do we find out if your pelvic floor is weak?

It is impossible to determine the strength of the pelvic floor without an internal examination using a device called a Peritron. This, along with a physical assessment will help to determine what muscles are either weak/long or overactice/short and will help direct treatment.

How can physiotherapy help?

Often women find it difficult to contract their pelvic floor muscles, 50% of women will be doing a pelvic floor contraction incorrectly when using a verbal instruction. An internal pelvic floor biofeedback assessment is usually needed to help retrain the pelvic floor muscles and ensure the correct contraction is happening. Your women’s health Physio will be able to assist in correct activation, then direct you to the appropriate treatment technique.

There is a growing amount of evidence to show that pelvic floor exercise devices can help to achieve faster and more effective results for the pelvic floor. Bio feedback devices, vaginal weight and balls, or even electrical stimulation for very weak muscles can help stimulate the muscle’s strength and bulk.

Treatment guidelines suggest that any women seeking professional help for stress urinary incontinence, try a regular and a sustained program of pelvic floor physiotherapy exercises before resorting to more invasive options such as surgery.

Studies by Moreno et al. (2004) and Dumounin (2014), showed that pelvic floor physiotherapy exercises are an effective and low cost treatment for stress urinary incontinence. Furthermore in the most recent guidelines from the American College of Physicians (2014) stated that pelvic floor strengthening exercises have a high quality evidence base for stress urinary incontinence.

Practical tips for managing incontinence

Although a physiotherapy assessment and management plan is the most effective treatment, there are other practical ways in which you can help your incontinence.

- Fluid intake. Most women wil reduce their intake in an effort to avoid toileting, however this can actually place more stress on the bladder leading to worsening urge incontinence. Try instead, to sip small amounts regularly. Urologists recommend 80-100mls/hour.

- Try reducing caffeine and acidic drinks. Caffeine is a diuretic and can cause dehydration if not balanced with water and acidic drinks may irritate the bladder.

- Schedule your toilet breaks. Keep a bladder diary and work out how often you go and try to schedule these at routine intervals during your day.

If you are experiencing urinary incontinence or other pelvic floor dysfunctions please contact our certified Women’s Health Physiotherapist, Jessica Findlay for an appointment today.

References

- Nonsurgical Management of Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. (2014). Annals of Internal Medicine, 161(6). doi:10.7326/p14-9034

- Dumoulin, C., Hay-Smith, J., Habée-Séguin, G. M., & Mercier, J. (2014). Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women: A short version Cochrane systematic review with meta-analysis. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 34(4), 300-308. doi:10.1002/nau.22700

- Moreno et al. (2004) Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics and Gynecology [01 Jan 2004, 31(3):194-196]

by Jessica Findlay | Aug 24, 2021 | Exercise, Postnatal, Pregnancy |

As a women’s health physiotherapist I frequently get asked about what type of exercise to do, how much to do, what is safe and how to return to exercise in pregnancy and postnatal period.

Below you can find all the evidence-based answers to the commonly asked questions that I get!

What is a safe amount of exercise to do during pregnancy?

The current 2016 RANZC exercise during pregnancy guidelines recommend that pregnant women should aim to be physically active, preferably all days of the week and should accumulate between 150-300 minutes of moderate intensity exercise per week. Exercise should be at least 30 mins at a time but it is advised to limit duration to 60 mins, unless the exercise is at a light intensity.

We encourage women to begin some type of exercise during pregnancy, even if you have not exercised prior to pregnancy. We would recommend if you are just starting out, to have guidance from a women’s health physiotherapist and to gradually build up over time. If you have already been exercising it can be a good idea to check that your current program is appropriate.

What is a safe intensity to exercise at?

Exercise intensity will depend on your baseline level of fitness and previous exercise routine. For those who have been previously inactive and are starting a new exercise program, maintaining a moderate level of intensity is recommended.

There is currently no evidence to suggest that women who previously participated in regular high intensity exercise and who continue to participate in vigorous exercise, are doing harm during pregnancy. Provided that they adjust the routine based on changes in comfort and tolerance.

Athletes should be wary of excessive exertion as fetal well-being may be compromised above a certain threshold of activity.

The talk test is quick and easy way to gauge exercise intensity. Intensity is considered moderate if you can comfortably hold a conversation, or is considered vigorous intensity if you have a need to pause for breath during conversation.

What type of exercise should I be doing?

There isn’t a one type fits all approach to exercise, find an exercise that incorporates strength, flexibility and aerobic components, and most of all you should enjoy doing it!

Provided that there are no contraindications to exercise, pregnant women should participate in both aerobic and resistance based activity. Women should aim for two sessions of strengthening per week, on non-consecutive days. Resistance can be light weights, rubber bands or body weight and should be performed at a moderate intensity, slowly with appropriate breathing.

Some great forms of exercise when pregnant are:

-

Clinical Pilates: it is a great way to perform resistance exercise, and is tailored to the individual.

-

Walking is a good aerobic exercise but should be performed at a brisk pace.

-

Hydrotherapy is great in the later stages of pregnancy, especially for its weight supported nature. It also reduces lower limb swelling and oedema due to the redistribution of fluid. Prolonged immersion in waters above 34 should be avoided, and immersion at above this temperature during the first trimester is not advised.

-

Stationary bike/ Cycling

-

Swimming

-

Pregnancy yoga

-

Strength based gym classes.

Why we haven’t mentioned running and high impact exercises? You can participate in these activities if you were doing it regularly prior to pregnancy, however pregnancy is such a short time of a woman’s life, that avoiding high impact activity during this time when your body is experiencing ligament laxity and softening is a good idea. This can help to prevent incontinence and prolapse issues!

Activities to avoid whilst pregnant:

-

Heavy lifting

-

Hot yoga

-

Skydiving/ bungee jumping

-

Scuba diving

-

Activities with a high risk of falling or getting hit in the stomach

-

Activities that involve straining, holding the breath or

-

Working at a high and unaccustomed intensity

I would highly recommend at your next GP, midwife or Obstetrician review to ask if there are any medical issues that would affect your participation in exercise. As there are some conditions where exercise is not advised.

So what happens to the body during pregnancy? and why does this affect exercise?

Weight Gain:

A number of changes will take place during pregnancy. Women will generally experience 10-15kg of weight gain to account for the baby, the placenta, amniotic fluid and increase in blood volume.

Vascular:

Vascular changes will occur especially in the second and third trimesters, where the cardiac volume will increase by 70-80mls, the cardiac output will increase by 40%,the resting heart rate will increase and blood pressure will decrease. These vascular changes reach maximum around the 20-24 weeks.

With this in mind, rapid postural changes should be avoided, heat and hydration levels should be closely monitored and women should be aware of how to track their level of exertion. It is advised to perform a cool down after exercise and not to stop suddenly.

Relaxin:

Relaxin is a hormone that is commonly blamed for SIJ pain (also known as pelvic girdle pain) and ligament laxity during pregnancy. It is a hormone that prepares the lining of the uterus for the implantation of the embryo. Relaxin peaks at the 12th week and will stabilise to 50% of this level at 17 weeks. The Relaxin level will return to normal within hours to days of birth. However what we know is that joint laxity increases during pregnancy and is most marked in the last three months of pregnancy and 3 weeks postpartum (i.e Joint laxity increases even though relaxin levels stabilise at 17weeks).

Peripheral joint laxity does not return to normal ranges within the first 6 weeks post birth, therefore is advised to not participate in heavy joint loading exercises during these periods, such as jumping and changing direction.Women who have abnormally high levels of relaxin have been correlated to experience more pelvic girdle pain.

Venous Return:

As the uterus grows with pregnancy, the weight of the enlarged uterus may abstract venous/ blood return. Therefore pregnant women in the second and third trimester should avoid exercise lying on the back for prolonged periods of time. Try sitting or standing instead.

Those who experience light-headaches, nausea or feel unwell when they exercise flat on their back should modify their exercise.

Pelvic floor laxity:

Activities that involve jumping or bouncing may add extra load to the pelvic floor muscles and connective tissue and are best avoided. Pelvic floor Strengthening exercises are generally recommended.

What effect does exercise have on gestational diabetes?

Exercise is now acknowledged as an effective way to decrease insulin resistance and thus help control blood glucose levels. It can prevent gestational diabetes if performed throughout the entire pregnancy at least three times per week.

Women should eat about 1 hour prior to exercise, to help balance blood glucose levels.

Who should perform the pre-exercise screen for a pregnant woman?

A general practitioner and/ or obstetrician will advise you if you have any contraindications to exercise. Examples of these may include cardiovascular disease, poorly controlled asthma, poorly controlled diabetes and bone or joint problems. They will also advise you if you have a pregnancy related complications.

Expectant mothers must be conscious of pregnancy-related complications, such as bleeding, sudden swelling, abdominal and back pains or decreased fetal movements. At the onset of any of these, activity should be ceased and seek medical assistance.

Back pain in pregnancy

Back pain affects between 48-90 % of pregnant women. The most common locations are the sacroiliac joint at the back, and the pubic symphysis joint at the front. The lumbar spine and thoracic spine can also become painful however are generally less affected. Pregnancy-related Pelvic girdle pain is mostly likely to present between 18-22 weeks.

Will back pain get worse as pregnancy progresses?

Generally low back pain that is present before pregnancy will start to feel better as pregnancy progresses, but new onset back pain during pregnancy may progressively increase if not managed appropriately. In pelvic girdle pain, resistance exercises are generally prescribed to increase the strength and endurance of pelvic stabilising muscles, such as the gluteal muscles.

What is the pelvic floor and what does it do?

The pelvic floor is a sling like structure of muscles, ligaments and connective tissue (fascia) that supports and contracts to hold the internal and reproductive organs up high and enables voluntary control of the bowel’s and urine.

Should everyone be doing pelvic floor exercises during pregnancy?

Most women will benefit from doing pelvic floor exercises, not only for strength purposes but also to prepare you to relax the muscles during labour. The research shows that if you do pelvic floor exercises throughout pregnancy you will be less likely to be incontinent in the postnatal period.

The internal pelvic floor muscles will therefore be less likely to tear and have trauma if you can relax them.

Some women have the opposite of a weak pelvic floor, they can be too tight and over active! These women should not aim to increase pelvic floor tone and strength but rather have a strong focus on relaxing and letting go.

What are safe exercises to do in the post-natal period?

Remember that during a vaginal delivery some pelvic floor muscles and connective tissue’s have to stretch up to 600x their normal length. This is a significant amount of trauma and quite a shock to the system. Therefore in the early days postpartum, slow gentle walking is advisable.

Hormones that are present due to breastfeeding, can continue to cause ligament laxity, therefore it may take up to a year before your ligament laxity is back to normal. I would advise to limit unnecessary bouncing, running and heavy joint loading activities if you are still breastfeeding.

For pelvic floor strengthening before seeing pelvic physio, you could start your rehab by doing one pelvic floor contraction per week postpartum

For example:

- Week one postnatal, hold 1 x contraction for one second, Repeat x three sets.

- Week two, do 2 x contractions holding 2 seconds each contraction. Repeat x three sets.

- Week three, do 3 x contractions holding 3 seconds each contractions, Repeat x three sets.

- Progress as the weeks progress until you see your women’s health pelvic floor physiotherapist after week 6.

When should a post natal abdominal separation assessment be done?

I encourage women to be assessed in private practice, two weeks post delivery. This is to ensure appropriate management is commenced, and to make the most of healing time frames and hormone changes. An abdominal separation check may only take 40 mins and management can include abdominal bracing, taping, progressive strengthening and tips to avoid overload.

When should I get a postnatal Pelvic floor examination?

Generally at 6 weeks once medically cleared by GP or Obstetrician, a women’s health pelvic floor physiotherapist can assess the internal muscles. These assessments are very important for specific strength training depending on your pelvic floor presentation. From here measurements can be done to see whether you are ready to return to running, weight lifting, over head weights, standing weight, kicking, boxing, jumping etc.

If you need to book in to see Jessica for an assessment, please click here

This blog is based on the 2016 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists current recommendation guidelines for exercise in pregnancy.

For a more comprehensive guide see:

http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Women%27s%20Health/Statement%20and%20guidelines/Clinical-Obstetrics/Exercise-during-pregnancy-(C-Obs-62)-New-July-2016.pdf?ext=.pd